“There is a local legend about two lovers – a young woman and a Ki Puu Puu warrior – who were separated by war,” says Leningrad Elarionoff, a retired police officer whose family members have deep roots in the community. A storyteller who often repeats stories long forgotten of incidents related to local landscapes, he sits under a pavilion at Ulu La’au (the Waimea Nature Park), detailing how Ke Ala Kahawai O Waimea (the Streamside Trail of Waimea) is steeped in mo’olelo. The history and legends surrounding this trail date back to prehistoric Hawaiian history, when Waimea (Kamuela) was home to the Ki Puu Puu warriors.

“The warrior and his beloved were preparing for their wedding when he was called into battle. The warrior never returned,” Leningrad continues. “He was killed in battle. And according to legend, the young woman died waiting for the warrior’s return and was buried along the trail. It is said that she still walks the trail, weeping and searching for him to this day.”

“The young man was one of King Kamehameha’s Ki Puu Puu warriors. The Ki Puu Puu were a type of Hawaiian special forces that trained in the hills above Waimea,” says Leningrad. “The warriors were very good fighting with their hands and using their knuckles. That, combined with their ability to utilize the Hawaiian martial arts move Pelu, made them legendary!”

The Ki Puu Puu learned Pelu from an old Hawaiian man who lived close to what is now the Waimea Streamside Trail, on a hill known as Puu O’Pelu, or Hill of Pelu. Using Pelu, the Ki Puu Puu could injure an opponent’s back and make him useless. It was a move that made the warriors fierce and feared in battle.

“The Ki Puu Puu warriors crossed this very trail on their way to practice Pelu,” Leningrad affirms. “Some even believe that the path they utilized to get to the old man’s house was eventually named Puu O’Pelu Road.”

By 1943, the area would become home to a different brand of warrior. In November of that year, 40,000 exhausted Marines from the 2nd Marine Division arrived on Hawai’i Island. Traumatized by the 76-hour Battle of Tarawa at the Tarawa Atoll (Gilbert Islands), the 2nd Marine Division went directly from fighting a gruesome battle to building their own training camp.

Richard Smart, owner of Parker Ranch, leased 31,000 acres to the U.S. Military for $1 a year. Known as Camp Tarawa, the dusty grounds of this campsite were located between the looming peaks of Maunaloa and Maunakea. And if the foliage isn’t too dense, you may be able to catch a glimpse of Mr. Smart’s house while walking on the Ke Ala Kahawai O Waimea Streamside Trail today.

After the 2d Marine Division left for Saipan, the 5th Marine Division moved into the base to train before being deployed to fight in the Battle of Iwo Jima in February of 1945. By November of 1945, the base was closed permanently.

From the Ki Puu Puu warriors of ancient Hawai’i to the Camp Tarawa Marines, the Streamside Trail (a Waimea Trails and Greenways Project) keeps their memory alive, and in turn preserves the lessons we can learn from their stories.

“Understand that the legend of the Ki Puu Puu warrior and his lover aren’t just told to explain the bones that were found here when preparing for this trail.” Leningrad points out. “These mo’olelo are meant to pass on a lesson. The young guys are the ones who suffer in battle. So when you make a decision, you need to consider who will be affected as a result. That’s the lesson.”

As for the bones, a state archeologist identified them as indeed belonging to a young female. On August 16, the bones were relocated to a more prominent location.

Connecting Waimea to Culture and Nature through Active Transportation

“Waimea means ‘There’s something in the water’ and refers to the yellowish color in the Waikoloa Stream from the hapu’u plant’s pollen,” Leningrad explains.

A center of ranching activities and paniolo culture, Waimea is a growing community whose economy is based on agriculture and a growing tourism market. Unfortunately, historic Waimea is bisected by a four-lane highway, Hawai’i Belt Road, which hinders biking and walking.

“With a lack of walking and biking infrastructure, people couldn’t walk safely,” says Clemson Lam, Waimea Architect and Ke Ala Kahawai O Waimea Committee Chairman. “But in 1994, Main Street Waimea (a promotion of Kamuela business organization in Kamuela) was tasked with developing a program in Waimea. Out of that, we got a better idea of what people like and do not like about Waimea.”

The majority agreed that they liked Waimea’s beautiful places, but were frustrated that there were no trails providing access to those places.

“No one could reach those places without trespassing to get to them,” Clemson recalls. “People wanted three different types of trails to access those places.”

The trail types included:

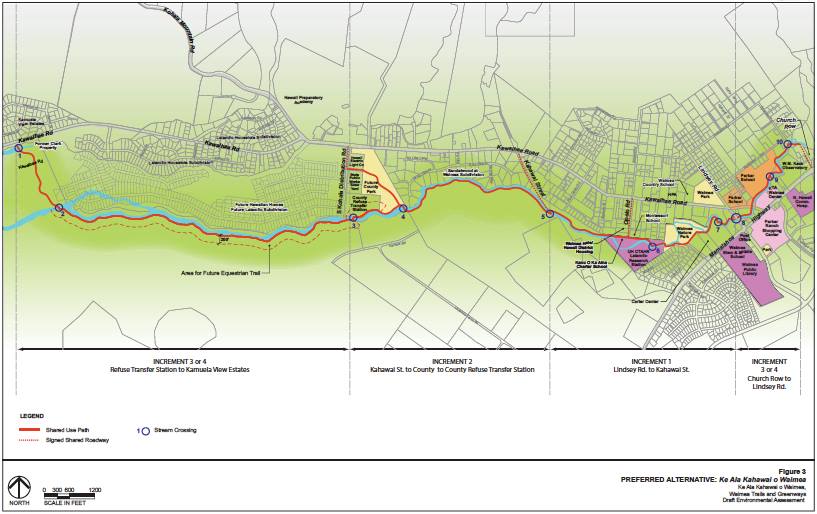

- A linear transportation corridor running east to west, for biking and walking to and from work and school safely.

- Existing trails across private land that could be used by the public.

- Trails connecting Waimea to other communities such as Waikoloa and Honoka’a.

With this clear definition of the community’s needs at its core, the Waimea Trails and Greenways committee was formed in 1994, meeting every Monday to look at streets, trails, and other relevant data. And Hawai’i County even hired a consultant to conduct a study and number all the trees in 1998.

In 1999, Ulu La’au was established by Waimea Outdoor Circle. And plans for the trail to safely, conveniently connect the Nature Park to schools, cultural centers, and local businesses in Waimea and beyond were moving forward slowly but surely. Unfortunately, the lengthy study of 1998 expired before action could be taken to build the trail.

“As a committee, we were frustrated. But we had the easements, so we rolled up our sleeves and got to work building a trail! We put up a fence. We counted the number of people that walked on sidewalks at different times of day. With the hands of the community volunteers, we began to build the trail!” Clemson exclaims, detailing the work day that was organized in 2008. It took 115 volunteers four hours, but by the end of the day, Waimea had a new trail, running from Ulu La’au to Opelo Road.

“Our committee still meets once a month because there’s more work to be done. Our main focus now is to keep Hawai’i County engaged,” says Clemson. “The county has agreed to adopt the trail, which is great news! And Mayor Roth has been very helpful with this.”

PATH

PATH is committed to elevating the efforts of community groups and Hawai’i County to create more multi-modal trails for active transportation in Hawai’i, with an emphasis on developing more protected places for people to use mobility devices, walk, or bike on Hawai’i Island. Next week, we’ll look at the great progress that has been made on the ongoing Ke Ala Kahawai O Waimea project, how the community and county can work together to open up Waimea’s Streamside Trail, and more!